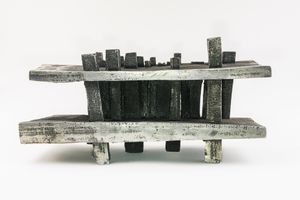

HENRY MOORE 1898-1986

Upright Motive: Maquette No. 1

HENRY MOORE 1898-1986

Upright Motive: Maquette No. 1

1955

Stock Number: 14723/MB

Height

31.00cm

[12.20 inches]

Sold

Artist's Resale Right applies @ plus 4%

Bronze

Date 1955

Ed. 10 (unnumbered edition), inscribed ‘Moore’, LH 376 cast g

LITERATURE

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore Sculpture and Drawings, vol.3, Sculptures, 1955–64, revised 2nd ed. (London: Lund Humphries Ltd, 1986), LH 376, ill. p.21 (another cast)

Between 1955 and 1956, Moore made a series of thirteen small maquettes known as ‘upright motives’, of which he would enlarge five as full-scale sculptures. The impetus was a potential commission for a sculpture to be sited in the courtyard of the new Olivetti building in Milan. To counter the architecture’s horizontality, Moore considered a vertical form rather than one of his characteristic reclining figures, but when he discovered that the sculpture ‘would virtually be in a car park’, he lost interest in the project. (1) Upright Motive: Maquette No. 1 (1955) would instead be enlarged as Upright Motive No. 1: Glenkiln Cross (1955–6), taking its name from the estate in Scotland where the first cast was originally located.

Upright Motive: Maquette No. 1 resembles a hybrid between a torso and an organic, asymmetrical cross, mounted on a slender pedestal. When creating maquettes, Moore frequently worked with natural objects, and it is possible that Upright Motive: Maquette No. 1 developed from the impression of a stone or bone pressed into clay or plasticine, combined with a solid column of plaster. The result has an aura suggestive of its potential to evolve or to generate further forms. Describing the enlarged version, the German critic Will Grohmann wrote,

The ‘Glenkiln Cross’ surely has more connexion with life than with death. … There is something swelling about the whole upper half of this ‘Motive’ that is more animal than vegetal. ... The observer wavers between animal and man, the sensual and the sublime, but the sublime [is] stronger – how else could the monument dominate the landscape? It dominates in a way in which a Christian cross stands watch over a landscape. … The monument is a symbol of something that exists, not something that ought to exist, and is full of disturbing life. (2)

(1) Henry Moore, cited in John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore (London: Thomas Nelson, 1968), p.245.

(2) Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, new enlarged edition (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1960), p.198.

Bronze

Date 1955

Ed. 10 (unnumbered edition), inscribed ‘Moore’, LH 376 cast g

LITERATURE

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore Sculpture and Drawings, vol.3, Sculptures, 1955–64, revised 2nd ed. (London: Lund Humphries Ltd, 1986), LH 376, ill. p.21 (another cast)

Between 1955 and 1956, Moore made a series of thirteen small maquettes known as ‘upright motives’, of which he would enlarge five as full-scale sculptures. The impetus was a potential commission for a sculpture to be sited in the courtyard of the new Olivetti building in Milan. To counter the architecture’s horizontality, Moore considered a vertical form rather than one of his characteristic reclining figures, but when he discovered that the sculpture ‘would virtually be in a car park’, he lost interest in the project. (1) Upright Motive: Maquette No. 1 (1955) would instead be enlarged as Upright Motive No. 1: Glenkiln Cross (1955–6), taking its name from the estate in Scotland where the first cast was originally located.

Upright Motive: Maquette No. 1 resembles a hybrid between a torso and an organic, asymmetrical cross, mounted on a slender pedestal. When creating maquettes, Moore frequently worked with natural objects, and it is possible that Upright Motive: Maquette No. 1 developed from the impression of a stone or bone pressed into clay or plasticine, combined with a solid column of plaster. The result has an aura suggestive of its potential to evolve or to generate further forms. Describing the enlarged version, the German critic Will Grohmann wrote,

The ‘Glenkiln Cross’ surely has more connexion with life than with death. … There is something swelling about the whole upper half of this ‘Motive’ that is more animal than vegetal. ... The observer wavers between animal and man, the sensual and the sublime, but the sublime [is] stronger – how else could the monument dominate the landscape? It dominates in a way in which a Christian cross stands watch over a landscape. … The monument is a symbol of something that exists, not something that ought to exist, and is full of disturbing life. (2)

(1) Henry Moore, cited in John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore (London: Thomas Nelson, 1968), p.245.

(2) Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, new enlarged edition (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1960), p.198.